As a Mainer and the daughter of an outdoorsman, I grew up being taught that ”camping” was a journey to enter Nature as deeply as possible. When I was a child, this journey, always and only spearheaded by my father, involved escaping from the comforts and obligations of home. At best, this meant an all-day drive to an uninsulated cabin with no electricity, no running water, and a distant outhouse. With loons, bears, an endless lake, and no other humans in sight, this sure looked like camping and wilderness to me. What did I know?

As I approached my teens, my father moved us to a new model of camping, one that involved a vintage red truck and a truck camper. In retrospect, this was kind of like a tiny home-man-cave on wheels approach to camping. Mostly my father used it to go hunting and fishing, but sometimes, while we were still hitting the 4-H show circuit, we would “camp” at the many fairgrounds spread out through rural Maine. Pretty handy if you want to sleep in the middle of lots of horses, cows, sheep, and pigs.

But sharing a roughly 10’X10′ tin can on wheels with a man whose flatulence etiquette needed some work lost its appeal during my teens. I think you can forgive me for this. My escape into the wild–and as it turns out, into the arms of my future husband–took a more austere and physically challenging path. Camping came to mean that you carried on your back a small tent, a sleeping bag, and all the food and water you planned to consume. Then you practiced the art of finding a small ledge on a mountainside where you could set up the tent–preferably not in the dark–while praying for starlight rather than biblical deluge.

By the time I moved from Maine to California for the first time, my tent camping experience evolved to car camping. This is almost the same as mountainside tenting, except that you don’t have to carry everything on your back and you can escape to the car if Nature and her locusts really turn against you.

This summer, I was reminded of all of this when I faced the unenviable challenge of needed to cross the country in a pandemic to reach family. The only way I would consider doing this was if I could avoid air travel and go the driving-camping route instead. No contact with people. No shared air with anybody. Imagine a self-sufficient bubble–complete with food and water–dashing across the continent with stops only to refuel and to sleep. My first thought was to rent an RV. I imagined a return to the truck camper, but way more upscale so that cooking, rest rooms, everything could be along for the ride. That didn’t work out well because everyone else had the same idea. RV rentals were either all booked or the price looked more like a flight to the moon or possibly a down payment on buying one. So car camping it was.

This trip reminded me of something that my own journey has taught me: “camping” is a very cultured experience, one that people imagine and carry out in remarkably diverse ways. Camping exists somewhere in that space between the poles of city and country, between home and wilderness, and between Nature and technology. There’s nothing like a drive across the United States to help you discover where you fall along the continuum between these poles.

Roadside car camping is where you fully face the spectrum of traditions. As a practitioner of tent camping, you know you’re on Mars when you have to thread your way through the RV section. This is the section where the long campers are parked parallel and close to each other. Sometimes, it’s paved like a parking lot. Other times, the long trailers are flanked by manicured lawns, side decks, string patio lights, satellite dishes, cookout grills, lawn ornaments, and bird baths. I could go on. By the time you reach the back corner, where maybe there’s a tree if you’re lucky, you’re feeling pretty far from that country/wilderness/Nature end of the continuum.

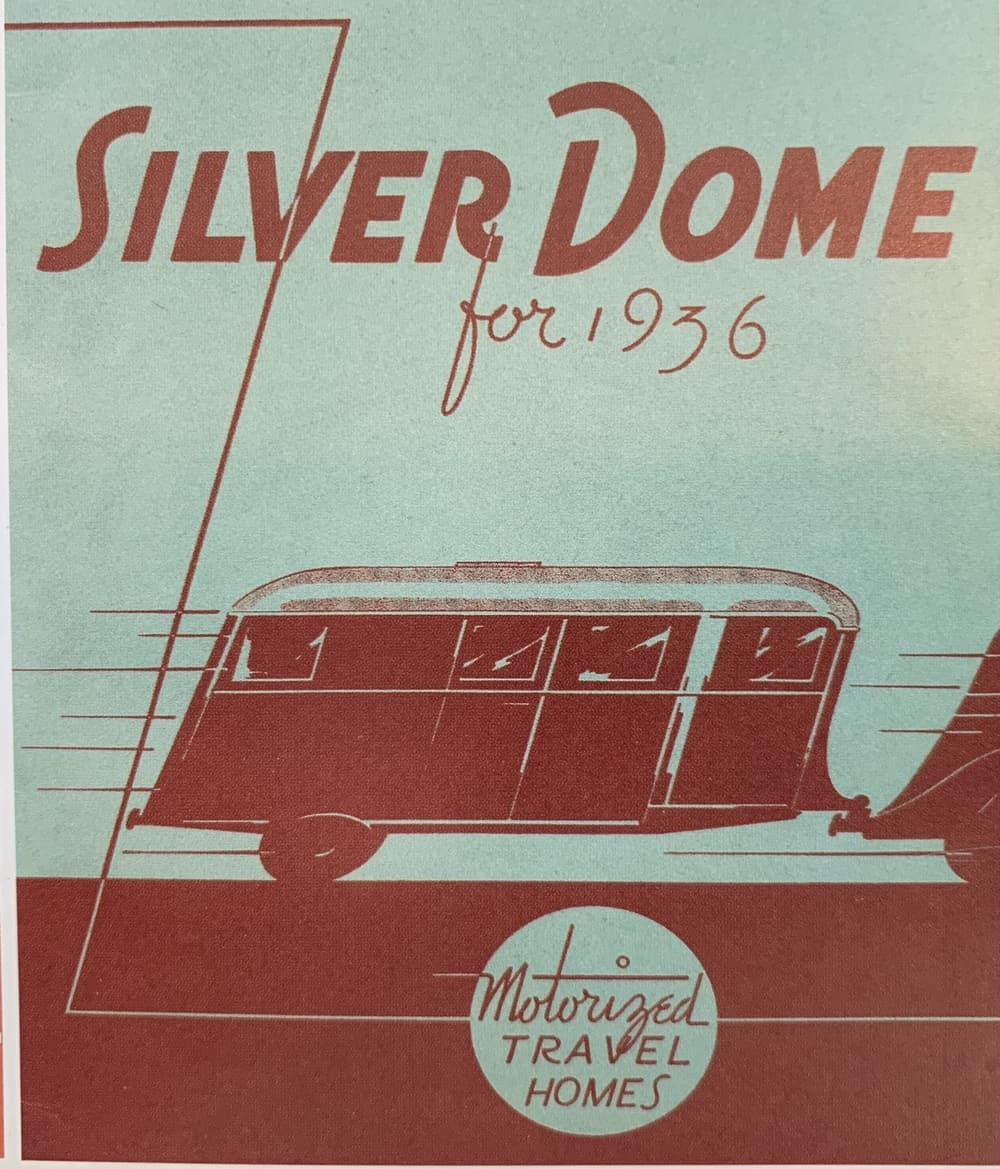

This got me thinking about the history of the RVs and how we got to a place where “camping” starts to look like reproducing one’s suburban neighborhood all over again. Even before the iconic Airstream of the 1930s, there were “transportable bungalows” and Motor Bungalows and the Curtiss Aerocar, not to mention Deluxe Covered Wagons. In other words, not long after automobiles were invented, families started retrofitting them to become motor homes. For some, this was for recreation and pleasure. For others, this was a way to cope with being homeless or following migrant labor and war boom job opportunities.

This summer, it was the pandemic rather than the Dust Bowl that drove my husband and me westward and then back again. The car carried the tent, the sleeping bags, and all the food and water that we planned to consume, rather than our backs. But, there were moments when the rain drummed on the tent fly and I had to shift my sleeping bag to avoid the puddle forming on the tent floor. There were moments when high winds yanked at the tent dome and sent it bucking wildly against its stakes. There were moments when I furtively snuck a peek at the warm glow of those string lights and cheerful RV windows. Just don’t ask me to admit it.

Patricia Erikson blogs about Maine writers, travel, and science from the award-winning city of Portland, Maine. If you haven’t already, follow her on Instagram at @seashorewrite or subscribe to Peaks Island Press in the upper right corner at http://www.peaksislandpress.com

Categories: Travel & travel writing

Enjoyed your pandemic tenting journey across the U.S.! Hopefully you were able to stop in some spectacular places on your way to visit family. Great story. Chuck Radis

LikeLike

Yes the Tetons were stunning!!!

LikeLike